Albania and its capital city are being transformed thanks to an ambitious urban redevelopment plan. Joni Baboci – senior advisor of urban planning at the Municipality of Tirana – tells Vanessa Norwood more.

Albania is on the cusp of change. Led by Prime Minister Edi Rama - a charismatic and controversial leader who painted capital city Tirana’s grey, communist era buildings in bright colours – the eastern European country has emerged from the isolation of its Communist past and is now in talks to become a member of the European Union.

Alongside Tirana’s mayor Erion Veliaj, Rama has overseen a transformation that has culture at its heart. It would have been easy to approach Tirana with a conservationist approach (the city boasts a noteworthy collection of historic buildings as well as brutalist masterpieces) but the vision was bold and some of Europe’s finest contemporary architects were invited to lead the change.

Stefano Boeri’s masterplan will see an orbital forest of 2mn trees around the city, whilst 51N4E’s restructuring of Skanderbeg Square has created a vast public space at the city’s heart. Tirana is fast becoming a modern metropolis with attributes that, during the pandemic, are acknowledged as more important than ever: democratic public space, proximity to nature and the prioritisation of people over cars.

As senior advisor of urban planning at Tirana’s municipal government, Joni Baboci has been a key player in the transformation. He tells the Building Centre’s creative director Vanessa Norwood about the city’s ambitious plans.

VN: Joni, can you tell us about your background and your role for the city?

JB: I was born in Tirana and always had a fascination with the city. I studied Architecture in Toronto and Cities in London. After a brief and uneventful stint in the private sector, in 2013 I led a small central government start-up called Atelier Albania. It was commissioned to rethink the territory of the country – a visioning exercise for the future of Albania on national and regional scales.

In 2015 I was invited to lead the urban planning and design team of the capital of Albania by Erion Veliaj, one of Tirana’s youngest ever Mayors. [I was] overwhelmed at the sheer complexity of the job and the multidisciplinary challenge ahead of me; I struggled with the idea of leading a group of more than 100 engineers, designers, and planners, most of them older and more experienced than me. The last five years have been a fantastic trip through the potentials and risks of city-making but, most importantly, a special privilege to have had a direct impact on my hometown.

We were able to deliver and coordinate urban design projects at all scales including Skanderbeg Square, the New Boulevard, the New Bazaar, Air Albania Stadium, Pyramid of Tirana, two dozen new schools and more. We redesigned the planning system, not only making it thoroughly flexible but transforming permitting and development as well by implementing electronic systems of checks and balances, increasing transparency and predictability while enforcing fair and cost-effective rules for development.

VN: Skanderbeg Square was the first major project started by Edi Rama as Tirana’s mayor with an international architecture competition won by 51N4E in collaboration with Albanian artist Anri Sala in 2008. The square was one of five projects shortlisted for the 2019 Mies van der Rohe Prize for the best building in Europe. The square is both vast empty space and beating heart of the city with a landscape of 12 micro gardens made of new and existing trees. How is the square being used and has it changed in ways that you didn’t anticipate during the pandemic?

JB: Skanderbeg Square is our pièce de résistance. We transformed the largest car-centric roundabout in the Balkans into a fantastic green, and exclusively pedestrian, square. 40,000 square meters of asphalt became Tirana's biggest playground where everyone can enjoy public space in cleaner air with the musical background of the hundreds of urban songbirds inhabiting the square's trees. I think that was the most shocking change to me – having walked through the square for a decade, managing its persistent traffic – was the quietness. Being able to hear, in the centre of the city the chirps of a bird or the buzzing of a bee, while enjoying a tangerine picked from the multitude of fruit trees.

The square is unpredictable. It has hosted the largest open-air concert in the city, but also provides flexible, private space through its movable urban furniture. It can be as intimate an urban nook as any space in the city. It's seasonal in functions too: a water-filled playground in the summer, a cozy garden in the winter. One interesting thing that stands out is how politics has not been able to usurp it. While large spaces in Tirana have often been used for political rallies, it is the one thing that has not happened in the square in the past five years.

VN: Boeri talks about the reclamation of the natural in his masterplan and states that the Tirana 2030 Plan will reduce the forecast for demographic development of the urban area by two thirds in favour of a green city. Can you explain how this will work?

JB: Rather than reduce, the TR030 plan provided for realistic future growth. In the fragmented administrative reality of the past decades, Tirana was a small exclusively urban local government unit, surrounded by neighbours who exploited their proximity to the centre; densifying the periphery. Five years ago the territory of Tirana grew by 25 times. It became an urban-rural-natural municipality. In tandem with Boeri we reimagined how a city could grow in this new context, in harmony with its surroundings. In the past 30 years Tirana grew from a city of 200,000 to a metropolis of 1mn. Most of the growth happened at the edge, consuming the agricultural and natural legacy of the city. The new plan prohibits any new development in the periphery, marking a clear boundary - but then allowing citizens to meander through the periphery in the more than 400,000 new trees planted in the last couple of years.

Having preserved the edge, we focused our attention on the centre. Rather than a static masterplan we designed a flexible and malleable system. In what we term bounded flexibility, architects can bend some rules if they are providing more public space when densifying the city. For example, you can build a couple of floors higher than what is foreseen by the plan but each extra floor comes with strings attached: more public space on the ground floor, more accessible amenities, more local taxes. It's a quid pro quo between the city and the private sector. It is a system which manages to find a fairer balance between the multitude of interests which drive urban growth.

In a similar fashion, one of the main strategic projects was the creation of dynamic urban polycentres. The plan tries to break the historical monocentric organization of the city by outlining a set of well-connected focal areas within the urban core to serve as secondary centres. Density around these areas is higher providing an incentive for private capital to intervene. Furthermore, the plan foresees important infrastructural as well as public services capital expenditures in these areas. The concept revolves around creating a critical mass of public and private investment helping these areas become magnets for the surrounding neighbourhoods.

Our plan is a resilient living document which future political actors can fit within their policy agendas, as long as they abide by its major tenets.

VN: The giant concrete pyramid built by Enver Hoxha’s daughter as a museum devoted to his legacy acted as a super-sized climbing frame with young men and women scaling its sides to reach the top. The abandoned structure will be given new life by MVRDV as a technology education centre. Given that Albania’s population is the second youngest in Europe, were their needs given particular attention?

JB: The Pyramid of Tirana was constructed with the aim of serving as a museum for the legacy of communist dictator Enver Hoxha. It fulfilled this purpose for three years up to 1991; since then it has gone through an array of functions becoming – always ephemerally – a convention centre, a national jazz festival venue, a lecture hall, a theatre, an exhibition space, the potential site for the parliament of Albania, a cultural centre, NATO’s HQ for operation Allied Harbour and a concert venue – all of this while always narrowly escaping demolition.

Through our collaboration with the TUMO centre [a centre for creative technologies first established in Armenia] we are shaping the Pyramid into an educational epicentre for the youth of Tirana - providing training in design, programming, robotics and other creative skills to underserved young-adults in the city. The Pyramid will equip students with the relevant fourth-industrial revolution skills before they even choose their subject at university.

The project doesn't only provide a fantastic and timely didactic infrastructure, it also directly confronts the structure's legacy. It is a symbol of the radical change that the Albanian state has been going through over the past 25 years: from totalitarianism to an open society, cultivating a fragile democracy. It challenges the building’s dark history with the hope of hundreds of bright youngsters designing the future. It's not just a reminder of the past, it’s a tale for the future.

VN: Tirana has an impressive collection of state buildings including the National History Museum, the National Theatre of Opera and Ballet, and the National Library. A new building comes with clear parameters for programmatic use. Have the existing buildings presented a challenge in terms of re-energising or reuse?

JB: Tirana is a mix of old and new: buildings, people, politics. But differently from most cities (where you have clearly marked historical boundaries in the urban fabric) Tirana is a wild geographical mix. The dichotomies are everywhere. This might however make the city more resilient and more easily adaptable to change. I think it is a challenge to design buildings in our present reality. We're stuck in transition – and I don’t mean just in Tirana. The extreme political dichotomies, the informational warfare, the technological transformation of the past 10 years make it difficult to preserve the temporal stability needed to design the functions of a new building. I think that is also the challenge of these structures: what a library represented 10 years ago is wildly different for what one is today; one can only imagine the function such a building might have in 10 years. We’re all waiting for the world to go back to being stable and predictable – and I don't mean just from the pandemic, or politics in general. But the more time passes, the more it seems like the new normal will not look like the old one. Embracing instability isn't easy but I think that is exactly what the future of these buildings will look like. They can’t be ‘designed’ in the old, finite sense. They need to be nourished and grown by communities unaffiliated with the political realm. They need to work as islands of history, ballet and books, driven by professional and passionate individuals. They need to attract a new generation of learners that can then become the apprentices for the future for these buildings.

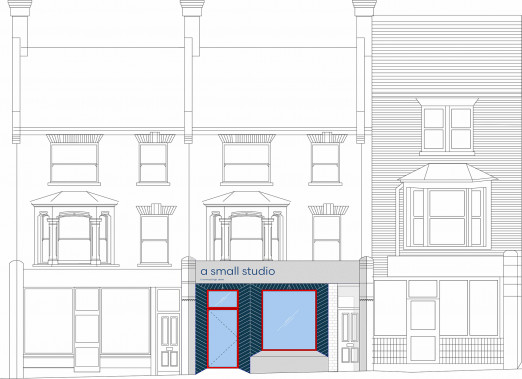

VN: Servete Maçi’s primary school located in the centre of the capital is a wonderful example of a new building in a very dense urban context. Can you tell us a little more about the Schools programme?

JB: When I was attending high school in Tirana 15 years ago, I shared similar difficulties to our current challenges: crumbling educational infrastructure and studying in shifts due to a lack of available seating in classrooms. All major educational research proves that studying in the second afternoon shift and lack of infrastructure, have a huge impact on the quality of education pupils are getting. That is why we are building more than 20 new schools, all of them to be completed in the coming years. Furthermore, these are not your typical schools: world-class architects are designing them from the ground up as 24-hour institutions. In the morning they will provide brand new classrooms throughout the urban periphery of Tirana, serving the low-and low-middle income communities that have moved into the capital in the previous 30 years. In the afternoons they will transform into community centres, providing many sought-after sports fields, cultural venues, and training programmes to all citizens of Tirana.

Servete Maci is a great example of the potential to transform even small sites. It was designed by a local team of young architects. This music school is located on a site which is just 1,700m2. It was torn down and rebuilt in the same site but at more than double the size, with a friendly pedestrian drop-off entrance and all the amenities of modern educational infrastructure. It also illustrates one of our priorities: to build a child- and caregiver-friendly city. The courtyard is lowered one full storey compared to the street. This makes it possible for the students to be in a semi-enclosed safe space. This particular area can be accessed from a public external staircase which also serves as an open auditorium. In a similar vein to resiliency, some elements of the school have numerous purposes, that can be changed, transformed or even temporarily removed. It could easily be called a community building that temporarily serves as a school during the day, and contains various other uses in the afternoons.

VN: Most cities globally have proved challenging places to live during the pandemic. Will all the recent changes alongside the Tirana Plan future-proof the city?

JB: I think rather than future proof we are trying to build a city that can at least handle the unknown. Urban systems exhibit stability brought about by multiple contingencies. Resilience is inherent to complex systems – the more redundant a system is, the less it is prone to fail completely. One interesting example is the variety of agricultural plots in olden villages where households farmed small strips of land in different ecological micro-zones. This meant that a family would have to tend to a dozen different crops located in various locations. While this strategy might be inefficient, it also distributed risk and therefore hedged against the ultimate threat: total crop loss & famine. Cities similarly adapt through a large number of small bets. This is a rather conservative model but in the long term it is the most efficient.

From this perspective we have attempted to look at urban interventions through the lenses of acupuncture and tactical urbanism. Of course there is Skanderbeg square, but we have also been able to co-design with communities more than 60 playgrounds, which (similarly to our schools) are places where neighbours meet, mingle and exchange. They serve as small-scale, community-based support systems – and thanks to our good weather, were a key urban space in confronting the pandemic. In terms of mobility we have widened walking pavements, popped up tens of kilometres of bike lanes, and built protected bus-lanes. The multimodal shift away from the automobile, hedges our bets towards what the future might bring. I think planning should at best attempt to stimulate new sequences: local, small-scale, diverse. If any prove successful the city will slowly metabolize them in the long-term. Cities are living entities always changing and adapting to new environments. They do not have resting points and do not strive towards any simple kind of equilibrium. Constant adaptability is a feature of long-term success.