Creative director Vanessa Norwood interviews A Small Studio to discuss how starting small with big ambitions can bring about positive change to our beleaguered town centres.

Tell us a bit about A Small Studio?

A Small Studio is an architecture, landscape and planning practice based in London. We build at different scales, with a high level of public and user engagement early in the design process and we teach landscape architecture and urbanism at The University of Greenwich.

The studio was founded in 2011 by Dr Helena Rivera, who specialises in the British planning system, with a community-focused ethos. The studio believes architects have a social responsibility to the public, a technical responsibility to the structure and a responsibility to protect the built environment by promoting a circular economy through its projects.

This year with our students we are exploring the minute pandemic-proof town, capitalising on the fact this cohort of students will be the first designers graduating after the COVID-19 pandemic.

How did the project begin?

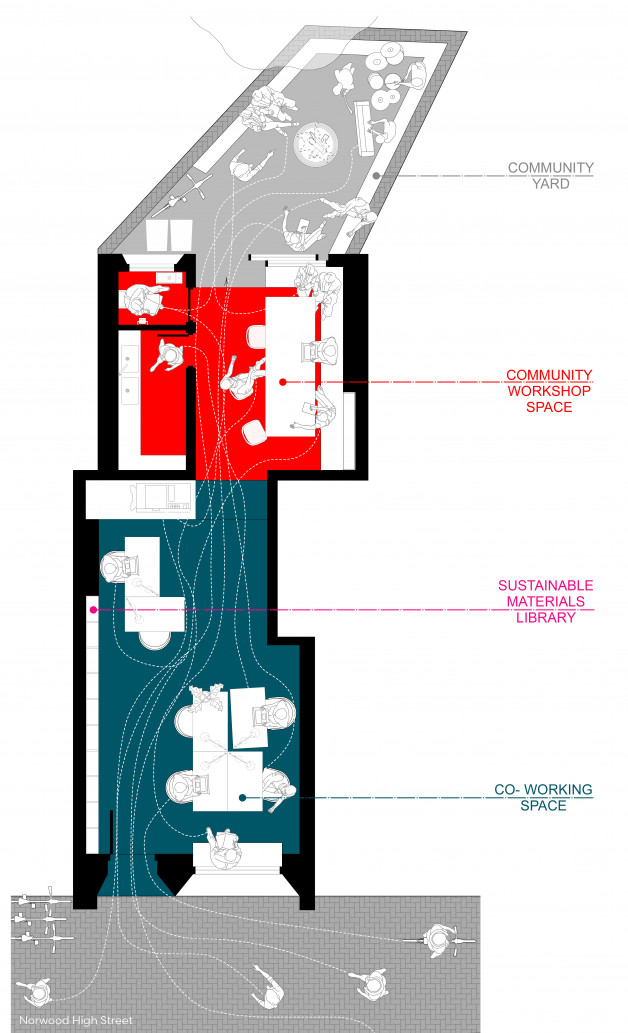

A Small Studio has worked in South London for a decade and has always wanted a workspace that was closer to the community and not working in a silo within an office building. We struggled to find anywhere suitable. Finally, in 2019 we made the risky investment of buying an empty, run-down shop that had been vacant for years on a declining high street. We envisaged refurbishing this shop into a creative co-working space, with a community room for workshops and meetings. Siting our business here would support local retail and services by bringing people into the area during working hours and regenerating a run-down strip of the high street where there is currently little sense of place.

The proposal would have improved current facilities by refurbishing and upgrading an empty and abandoned shop and increasing the number of people working in the area who need affordable and flexible working space locally. However, this was a complicated process: The Local Authority didn’t understand the changing needs of retail and continues to be fixated on the Local Plan which insists on a retail frontage along the high street. But times are changing! Retail is in crisis; flexible working is on the rise and consumers want experiences as well as shopping. So, at A Small Studio we wanted to address this challenge by using our empty shop as a pilot project.

In Norwood High Street there are key sites available for affordable housing and developer-led projects, but we want to ensure the street level remains in use by and for the local people. This means affordable workspace, parks, pop-up venues, ecology walks, cafés, innovation hubs. We needed to ensure the local makers, artists, school-children, freelancers, young families, small businesses and senior citizens have a high street that serves their needs.

We saw the opportunity of leading a month-long digital consultation during the month of June as part of the London Festival of Architecture 2020. The theme of the Festival this year was Power so we decided to engage with the local community to underpin the potential and power of Norwood High Street as a symbol for many similar London high streets in crisis.

We believe Norwood High Street and its surrounds could be re-invented as a creative and cultural link between Brixton and Croydon. Working with the local community and in collaboration with Station to Station, the Business Improvement District for Tulse Hill and West Norwood, A Small Studio proposed a radical re-think of the use of this high street.

What is Norwood High Street like?

Historically, Norwood High Street, in West Norwood, Lambeth, contained the earliest group of shops in the area but never developed into a major shopping centre. It was the period of horsedrawn trams that shuttled passengers along the road from the terminus in front of St Luke’s Church and West Norwood Cemetery towards central London. This High Street has suffered from post-war depopulation and a focus on this area being an industrial location. At the moment, it suffers from high vacancy rate and poor urban environment.

The area includes a mixture of warehouse, retail and wholesale, office buildings, railway arches and newly opened cultural facilities such as a newly refurbished public library, a Picturehouse and the local South London Theatre. The population in the area is made up of a diverse cross section of society by age, ethnicity and wealth. Over the last decade there has been a continuing influx of young people and couples with small children. There are a number of community groups and organisations actively working to make the area a better place. The most notorious is Feast, a monthly community event organised by local volunteers. This takes place at St Luke’s Church, in the format of a street market festival, which aim to bring together the locals.

What are the challenges facing the high street and this area in particular?

One of the major challenges that we identified in the area is that the high street has little footfall, making it feel dead, empty and abandoned. However, it is sustained with a flurry of (invisible) activity happening behind the scenes; railway arches parallel to the High Street are occupied by fine artists alongside small streets and alleyways filled with light industrial activity and food producers. How could we embrace all of this activity and widen the conversation about what highs streets actually were? So, one major challenge was how to broaden the conversation to include all of these tangential places and areas. We saw this falling into three new categories of public space and the creation of a new public square; incorporating the mixed-use fringe of artists and makers workspaces; and re-purposing the abandoned and empty high street shops by giving them a new lease of life mainly through a change of function. Opening up this discussion in the community consultation was easy – exciting even! – and hugely embraced by the stakeholders and residents. However, since we had the shop as a pilot project running simultaneously, we quickly realised that it was much harder to convince the Local Authority to widen the high street conversation and think beyond the Local plan.

At the moment, it suffers from high vacancy rate and poor urban environment. Many of the commercial premises on the high street have been converted into housing through a slow and gradual conversion with no planning consent, and the Local Authority has not issued enforcement notices against this. This means that changing their use back into commercial spaces or encouraging public spaces will be nearly impossible. The damage this creates to the placemaking of the area is significant since it removes active street fronts, the possibility for having nigh time venues and the local community has few spaces where to go locally.

What were the challenges beyond buying the site? You spoke about the Local Authority – what is their view on the High Street?

Getting planning consent towards the conversion of a commercial premises (classified for an A2 use only) into a business (B1 use) or mixed scheme (Sui Generis) with the site located on the high street was very difficult. This was before the Prior Approval changes coming to place, nonetheless Local Authority Planning Departments could not understand how removing a commercial use could be part of a bigger regeneration strategy.

When we tried to (legally and officially) convert the empty abandoned commercial premise into a mixed use workspace (including office space, a community hub and a community workshop yard), the Local Authority rejected our scheme on the basis that it was removing a Commercial Space from the area and it went against the Local Plan. We had evidence to support the application, demonstrating that the unit as a commercial premise was into viable and the ‘use’ had to be re-invented, but this was a very long and difficult process.

How did you engage in local consultation?

We structured the local consultation themes based on the Neighbourhood Plan for Norwood that we have been working on together with The Neighbourhood Planning Assembly, which is currently writing The Norwood Green Town Charter. This is being written by a cohesive committee made up of local community representatives, residents and including a number of built environment professionals.The Norwood Green Town Charter sets out a shared vision and ambitions for the neighbourhood over the next 10-20 years and proposes a new Creative Enterprise Zone designation in the area. This is to redefine and revitalise the role of Norwood High Street for creative and digital enterprises, building on the proximity to the Commercial Areas, and heritage and cultural area in the town centre.

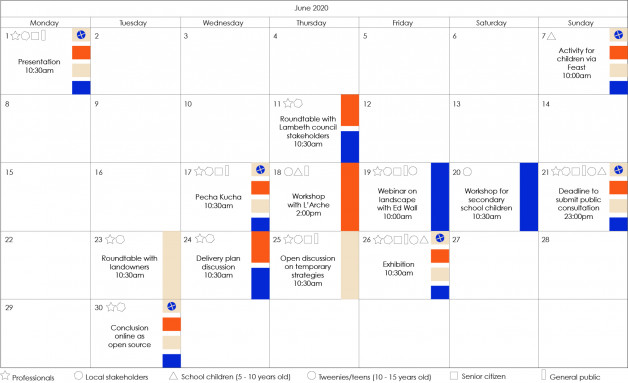

To ensure the community consultation would promote a citizen-led regeneration we used the Mayor of London’s ‘High Streets for All’ recommendations as a guide. We capitalised on the digital aspect of being in lockdown to organise a series of talks and web-based interactive workshops, we worked with different local demographics to get a wider (and more exciting!) series of proposals to revitalise and redefine the Norwood High Street.

We tried to keep the momentum of collective spirit that COVID-19 has created in local communities with the emergence of WhatsApp groups and neighbourhood help during lockdown. So, we asked the local businesses, residents, shopkeepers, landowners and children to participate in a wide and diverse number of activities. To ensure that different ages and interest groups could participate we organised children’s workshops, online polls, roundtables, open discussions, teenage 3D ‘real’ designing, seminars and presentations.

The main aim of this public consultation was to be as inclusive as possible; working with community groups, harder-to-reach citizens, local stakeholders, local practitioners and statutory authorities.

The programme culminated in an online exhibition to showcase the community result, which remains as an open data source available to everyone online. These results have been used as evidence base for the Neighbourhood Plan and as an incubator for local creative economies. Both of these aims are actively testing the resilience of Norwood High Street as a place of reinvention.

How has COVID affected the project?

The COVID-19 pandemic led to a lockdown that abruptly changed the project and emptied the high street even further. But this is an opportunity! COVID-19 is leading to an era of ‘hyper-locality’ to reduce commuting and provide local workspaces. The pandemic also created strong social support networks that are currently digital. Where will these migrate once the lockdown is over? How can community groups continue to meet and support each other if there are no venues? At A Small Studio we are using the COVID-19 challenges as an opportunity for innovation. Moving the groups from a virtual/digital platform into a physical space is an important part of that transition and we are hoping the refurbished off-license will act as a community hub where these interactions can continue in the form of Arts & Crafts workshops, local group meetings, co-working spaces and a material library specifically dedicated to the sustainable ‘circular economy’ materials available for refurbishment projects.

Tell us about your hopes for the project? How do you see it activating the street?

There is a personal interest because A Small Studio is the architecture firm leading the project, but there is a much wider concern/interest that we are pushing about how we can collectively work together to improve and change high streets. Thinking long-term, this pilot project has two different dimensions; a very practical example of shop conversion and change of use and a wider Neighbourhood Plan discussion (which we are a part of) about how high streets will have to change and adapt for a green, circular economy where hyperlocal working and living is needed.

Hopefully, on the one hand, this project provides a small-scale local pilot project for how empty shops can be re-purposed which would have large-scale regional impact if applied regionally and nationally (the number of empty shops in 2020 – before COVID-19 – was at a record high of 12%). On the other hand, the high street conversion has created a community space where we will host a programme of workshops and events that promotes the integration of the environmental climate change conversation into all our aspects of our life, targeting different ages and demographics.

We want to improve West Norwood, making it a permanent sustainable creative economy. This means taping into the existing vibrant and creative residents, professionals and existing business that make West Norwood the culturally rich and socially diverse neighbourhood it is. We want to promote a creative regeneration and placemaking of the neighbourhood whilst mitigating the gentrification witnessed in other London ‘successful’ areas.

We want to increase local collaborations and collectively strengthen the area’s local values. Above all, we want to see Norwood High Street become a genuinely mixed-used creative economy that – above everything – protects its local fine artists and small businesses.