Interview with CJ Lim, Studio 8 Architects

The Food Parliament by CJ Lim/Studio 8 Architects with Martin Tang, Pascal Bronner, Jen Wang, Geraldine Ng, Barry Cho

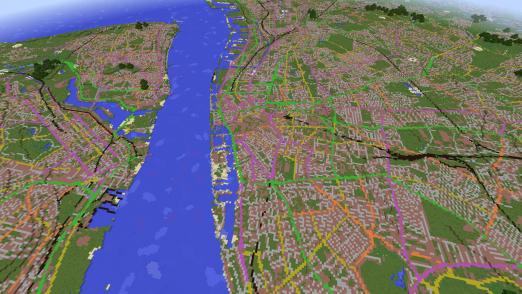

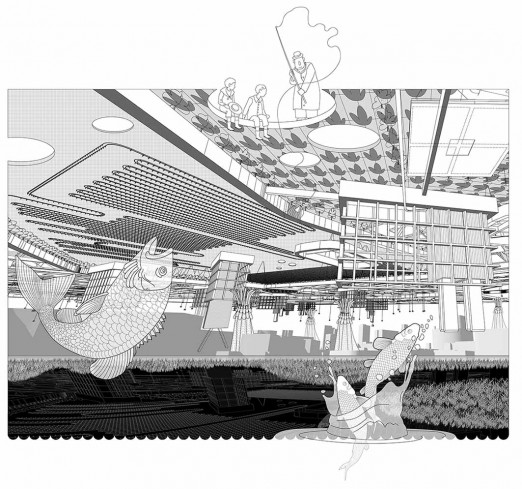

The Food Parliament is a set of polemical drawings that show how a radically altered city that focuses on food production could be a way to restructure employment, education, transport, health, culture, communities and the justice system. The freedom of drawing is used to deliver a radical investigation and challenge to existing notions of the spatial and political entity of cities.

In the interview below CJ Lim highlights just how pressing the issue of food security is going to become, why architectural narratives such as his are necessary and he reveals a surprising but fascinating illustrator inspiration.

Context

Can you tell us a bit about the Unit 10 course you teach at the Bartlett, and its themes that relate to The Food Parliament?

CJ Lim: Bernd Felsinger and myself have been teaching this Unit 10 course for over 10 years now, on the Masters program at the Bartlett. We have very different interests and points of view. Bernd is a director at Atelier One, they have built amazing huge stage sets and engineering infrastructure – the stage set for the U2 360 Degree world tour, he was involved in all that and in the stage sets for the Commonwealth Games, they do really innovative stuff. They have built amazing huge stage sets and engineering infrastructure.

I come from a world where for example I do planning in China and have my passion for narrative architecture. So we come from very, very different points of view and that makes it quirky, edgy and interesting at the same time. I think that chemistry works well. Also my pursuit of what is the definition of sustainability in the 21st-century is something he is interested in.

The Unit 10 agenda is to define what sustainability means. Sustainability has become such a generic word, developers to local governments to national governments all use the word without really thinking about it. We’re using sustainability as a way of looking into what the built environment could be in the future, and how we define it in relation to architecture and planning, but also in relation to culture, heritage, social issues and the ever-changing world of technology.

Although Unit 10 is very much into futuristic, visionary, utopic propositions, we deal with real concerns. Our scenarios start from the point of view of not offering solutions. We say ‘what if?’ How can we actually inspire a discourse rather than say, ‘these are the answers’.

(The Food Parliament)

Research

What was the inspiration for The Food Parliament? Could you tell us a little bit about the research that helped forge the project?

CJ Lim: The Food Parliament was a continuation of my previous book called Smart Cities and Eco-Warriors. That book was a series of planning commissions by the Chinese and Korean governments about 10-12 years ago now. We were disappointed at the time that the Chinese government were very happy to get rid of 12 to 15 km2 of food production land, to build a new city. We just thought, ‘You are going to house half a million people but where are these people going to get food from?’ And they said, ‘It’s not an issue, we are going to import it in from somewhere else’. As you know, in China now they’re investing so much in agriculture in Africa, shipping food from Africa back to China – imagine the food miles. They want to build eco cities, but they don’t understand that when they have to import food to feed that local patch of people, the eco-rating will drop.

Every part of government from local to national, must consider food as part of the energy equation. They have not done that. Food is always sidelined. They think we need wind power, solar energy, tidal wave energy and so forth, but never actually food.

Food also includes water, and water is going to be one of the most expensive commodities that we cannot do without, there is a lot of dirty water. Water that is not polluted or contaminated will be very, very expensive in the future. No government has suggested that we should really start looking into that area. So from those Chinese master-planning projects we thought, what if we fit that issue into a slightly different scenario, a scenario of a city like London. When I was thinking about this, there was this huge expenses scandal among MPs. I just thought we needed to make use of MPs – ‘how do we use political governments to play a part in the built environment, play a part in food security?’ That’s how the idea for the Food Parliament came about, the different parliamentary characters are turned into tectonic characters to serve a part of the city, to influence public place-making.

(The Food Parliament)

That was the beginning of it, we spent three to four years after that researching, looking at food security and safety issues in this country and around the world. I gathered hundreds of photographs and materials a lot of it was synthesized and put into play in the food Parliament. There was one project in particular that we were very much inspired by that was in Brazil – The Restaurante Popular. In Brazil there is a top-down policy (in this country it’s perceived that every top down policy is going to be bad and bottom-up policies are going to be much better). It gave me hope to see this Brazilian policy where every Brazilian citizen is entitled to a nutritious plate of food a day. Because of that they have kept the health level pretty high, so it’s cheaper to feed somebody than to treat them when they get ill. So through the Food Parliaments, through top-down governance, there could be social semi-equality, not total equality, that was the inspiration behind the project. It should be seen as a provocation, not a solution to be built tomorrow.

The Visual

Is it fair to say the visual language that you’re developing is more open, provocative, designed to spark wider debate?

CJ Lim: I think the visual language we are trying to develop are ones that can communicate beyond the architecture and design circles. We want to share with everybody, not everyone to be honest could read plans and sections in a conventional way. We want to use the visual language to draw people in, it’s very much inspired by artwork, posters, we want to draw on a wider range of presentation languages. It’s also questioning the domination of digital artwork in architecture where the computer has really taken over. We have become very dependent on that machine as a tool.

For me there is a degree of ‘danger’ in being so reliant on a machine, I like the romantic notion of crafting. It doesn’t matter whether you’re crafting a door handle, a roof, a whole building, or a drawing. We need to be able to craft the built environment with a huge dose of human nuance. I don’t live in a world where the quality of the environment is completely dependent on the software that you have. I have seen even with many of my architectural heroes in the late 20th century a tendency to start looking the same, because they use the same software packages.

If you all use the same tools you are reading from the same hymn sheet, there’s very little scope for creating diversity. Great cities like London, New York, Rome, Florence, Kyoto they are all created over different generations, each generation has a very different concern and I think that’s what makes great cities. Great architecture comes from diversity rather than everything coming from one perspective.

Making

What kinds of tools did you use and how did you decide on them? For example in your book London in Short Stories: Two-and-a-half Dimensions there was a lot of paper-cutting.

CJ Lim: For The Food Parliament we wanted to take a different direction than the paper-cutting in London in Short Stories: Two-and-a-half Dimensions. We wanted to use the tools to explore a different dimension of narrative. There was a lot of sketching. All the drawing that you see that are part of that series would be originally sketched up first.

(Sketches of The Food Parliament)

We then used Illustrator to draw the lines and Photoshop to put in tones. It’s a very straightforward process compared to the paper-cutting in London Short Stories: Two-and-a-half Dimensions where the paper cutting was akin to having a group of people sitting around a table and pushing a duvet!

The Food Parliament was done through a computer but very much dictated by the hand, very rudimentary hand-drawing, sketching it up, only using the Illustrator tool to draw the lines, then Photoshop. The drawings were then reprinted on textured paper because computer lines on glossy, shiny paper look very harsh. We wanted a softer quality – like drinking a soft wine versus one that’s acidic.

The Future

What is the impact of this kind of speculative architecture? What is its place in an age of climate change, food security, energy security?

CJ Lim: It allows windows of opportunity for broader discussion. I guess I operate in two worlds, I have the good fortune of doing research, experimental projects that question. Then there is this other world of real commissions by governments, there’s a real brief, and I realized that for me to do interesting work in the commissioned world I need to do these experimental studies – studies that actually do not give you all the answers. I need to open up avenues for discovering new creative knowledge. We would never have had the Pompidou Centre without Archigram, yet Archigram never built, they enabled other people to take up the mantle. Without all the experimentations that Zaha Hadid did in her early days we wouldn’t have get to enjoy her wonderful Phaeno Science Centre in Wolfsburg or the MAXXI Museum in Rome. It’s my role as an educator to provoke, and that’s what research should constitute.

A lot of people might know my hero is less Le Corbusier and more Heath Robinson. Heath Robinson was very prolific between the two world wars but he actually used his illustration to convey different points of view about important issues. He used incredible wit to engage people who were not very political. Through his illustration he managed to draw people in to have a political position, around issues of rationing, ‘making-do’. Now the enemy is global climate change, the sea-level rising, some of it is outside our control. Concerning visualisation one can engage everybody, and I want to believe that the way the profession uses visualisation we can bring in everyone from a 70 year-old grandmother, to eight year-old kids, to engage in what matters. It’s not just for the elites or the developers or governments but it’s important for everyone to engage – that’s what Heath Robinson was able to achieve.