This essay written by Vanessa Norwood forms the 'K' chapter of An Alphabet of Architectural Models, edited by Olivia Horsfall Turner, Simona Valeriani, Matthew Wells and Teresa Fankhänel and published by Merrell Publishers. Available to order online or buy in the Building Centre cafe for the duration of the Shaping Space - Architectural Models Revealed exhibition.

Kit. The word conjures up a travelling salesman moving from town to town, suitcase in hand. The infamous architect with a book of buildings ready to sell; a town hall here, an art gallery there – a kit of parts waiting to be built. ‘Kit’ makes it sound easy; nothing to suggest the deliberation, the slow, thoughtful design process or the specificity of site. Just pick something from the suitcase.

The word belongs to the realm of childhood; Lego, Meccano and Stickle Bricks assembled into swaying towers and unsteady bridges, ready to be demolished by unscrupulous four-year-old town planners.

Wooden building blocks have enthralled children for around two centuries. The German educator Friedrich Fröbel coined the word ‘kindergarten’ in the nineteenth century, and went on to revolutionize play with his design of a kit known as ‘Fröbel’s Gifts’. The kit contained geometric building blocks that are said to have influenced architects and artists alike. In the United States in 1913, the educational reformer Caroline Pratt took inspiration from Fröbel to create unit blocks, wooden bricks of different shapes and sizes that have encouraged generations of children to think modular, using the blocks as tools with which to explore the social and physical world around them.

Devotees of Frank Hornby’s eponymous brand of miniature trains span all age groups. Hornby presents a world of ready-mades to populate a village landscape at a scale of 1:76; it is a kit that evokes the 1920s England of its creation, complete with fish and chip shops, cricket pavilions and village pubs. Hornby’s first foray into kits had come twenty years earlier, when he devised Meccano, a model construction kit intended to teach children the basics of mechanics. Meccano enabled generations of both children and adults to make working models from metal strips, gears and wheels.

The appeal of the architectural model can be traced back to our childhood sense of awe at seeing the world miniaturized. A quick trawl of the internet will reveal that the market for architectural kits is booming. It is possible to buy a kit for a miniature Dutch farmhouse with a resin roof and ceramic walls, or, for those with more time on their hands, there is a matchstick modelling kit of St Paul’s Cathedral. Companies such as Arckit aim their architectural modelling system at kids, students and architects alike, with the explicit ambition to ‘open up the world of architecture to everyone’.

Kits make designers of us all. The ability to create townscapes in hours is a compelling challenge. The kit and its component parts create a connection to the process of building – a fixing-together with our hands.

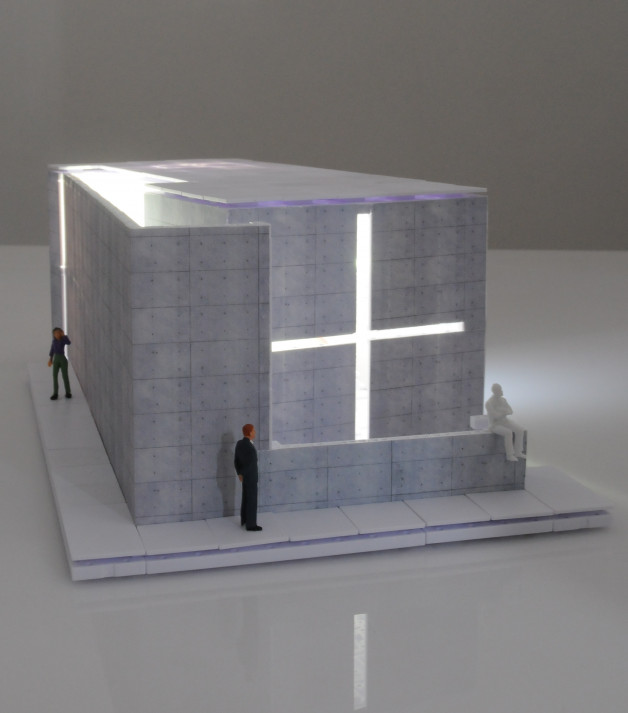

The scale of a kit can vary from toy to supersize. Kit architecture at a scale of 1:1 retains the magic of its scaled-down counterparts. First exhibited in Oslo in 2006, dRMM’s Naked House is a flat-pack kit designed to be built on top of the container in which the component parts were shipped. Naked House has the feel of a toy house on a massive scale, complete with a cut-out of a human figure. The idea of the house was that it could be dismantled, repacked and re-erected on a new site. It functions as a supersized cut-out diagram with elements numbered for construction, including door and window openings, all digitally pre-cut from substantial cross-laminated timber panels.

The kit provides a way of understanding the built environment piece by piece. In the 1970s Walter Segal popularized the self-build movement. Segal’s method proposed an architecture of components – a kit consisting of trusses, walls and beams – that enabled anyone with the most rudimentary knowledge of tools to build their own house through the acquisition of skills. Design was demystified, and architecture became a democratic pursuit. Segal used a Perspex model with moveable parts to help families create the best layout for their needs.

The first post-and-beam Huf Haus appeared in 1972; a sophisticated, customizable kit of parts using wood and glass as its building materials. More recently, WikiHouse, an open-source technology providing a digitally manufactured building system, aims to make it simple for anyone to design, manufacture and assemble their own home. Hawkins\Brown used WikiHouse’s flexible form to great effect at Here East for its transformation of the former Broadcast Centre in the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in London. The spatial and structural constraints of the building’s exterior gantry made the flat-packed modules the perfect choice as they could be assembled on site.

The conversation about the benefits of kit housing and larger-scale off-site construction is gaining momentum. A kit of factory-made components delivered to site ready to install offers distinct advantages over on-site construction, with its lengthy disruption and noise. Alongside retrofitting, the idea that, having reached the end of their lives, buildings can be dismantled and repurposed through the remanufacturing and recycling of materials is becoming increasingly urgent.

The kit is being developed further through new technologies. Block Type A, created by the Bartlett School of Architecture’s Automated Architecture (AUAR) Labs, explores radical new ideas of automating the ways in which we build. It uses robots to construct houses, disassemble them and rebuild them again in different contexts. Block Type A addresses the high cost of land and property and our inefficient use of domestic space by proposing a system that allows us to share both space and belongings according to need. It could be described as a kit to rationalize our kit.

The kit’s capacity for speedy construction was exploited by Extinction Rebellion during protests in London in October 2019. The protesters made use of easy-to-assemble wooden blocks adapted from Studio Bark’s U-Build system, and cut-outs enabled them to chain themselves to the modular structure once it was built. The kit transformed into an architecture of protest; a literal and metaphorical platform for action.

The kit provides a process that, with component parts, can enable the democratization of architecture. A sibling to the architectural model, the kit is both a system with rules and instructions and a collection of pieces. The opportunities to shape space are endless.