Interview with Rita Lambert, The Bartlett Development Planning Unit with CASA

(Mapping Beyond The Palimpsest – ReMap Lima: a project by The Bartlett Development Planning Unit with CASA, CIDAP and CENCA

This project designed to map and visualise two areas of Lima, Peru, sees academics and researchers working with the communities to give them tools that enable a better understanding of their environment and may support a more participative and sustainable planning process. Data captured by drone flights over the territories was used to create 3D printed forms onto which further information is projected.

The following Q&A with the team highlights the many different levels at which this inspirational project worked. While greater public participation increasingly seen as essential to successful planning this project yolked the latest technology to mapping and inventive public engagement. The result is not only a vision of better, more equitable landscape planning, but just as importantly, the project gave citizens a sense that space and planning really matters, and that they have the power to shape it.

Context

Can you explain to us a little about the origins and work of the Development Planning Unit at the Bartlett in collaboration with Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis?

Rita Lambert: As part of the research platform entitled Learning Lima established by Adriana Allen and myself, the Development Planning Unit (DPU) had been engaged in participatory action research in Lima since September 2012.

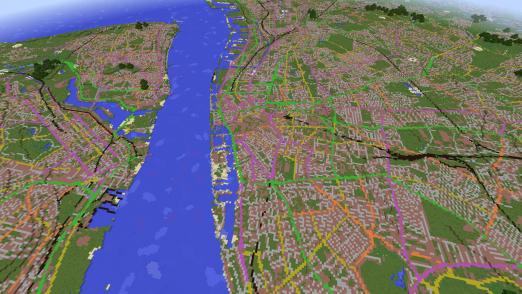

The research undertaken involved the use of maps and mapping as methods that help us to learn spatially, to better understand the causes and manifestations of injustices in cities, and to identify avenues to re-shape the unjust distribution of resources and but also the opportunities towards a more equitable future. In collaborating with Andrew Hudson-Smith from the Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis (CASA), we were interested in expanding the possibilities for spatial analysis in marginalised settlements that more often than not were non-existent in official maps. In particular we focused on the historic centre of Lima, Barrios Altos, and the periphery, Jose Carlos Mariategui (JCM) in San Juan de Lurigancho District. Both these sites have very different problems and are undergoing unwanted changes.

(The video above was produced by ScanLABS)

Traditionally the map and cartography has been conceived as something objective and quantifiable, could you explain how such notions of participatory and contextual mapping have evolved?

Rita Lambert: The project had two parallel processes which go hand in hand, mapping from the sky using drones and mapping from the ground where community mappers design transects and collect information. Although the drone image can be understood as an accurate representation of what is there in reality, the god's eye view, although revealing, also needs the interpretative aspect, which can only be completed with the stories, experiences and knowledge of people living in these neighbourhoods.

(The above aerial mapping was donated to the OpenStreetMap community by Drone Adventures)

Research

Did the Lima public ‘get’ the purpose of the project straightaway?

Rita Lambert: Yes, because the project itself was to an extent defined by the inhabitants from the two areas we were working in. We did not come with a predefined plan of what to map – this was decided together with the community mappers. Of course we needed base maps to work with which were an output of the drones – but what was then to populate these images from the sky was up for discussion. Our first question to the participants was: why map? Mapping was discussed by the residents as a way to apprehend their territory and a means to document and denounce otherwise invisible processes of unwanted change in their neighbourhoods. It was also seen as a strategic activity to foster dialogue between stakeholders and to expand the room for manoeuvre to promote strategic interventions. Once reasons of 'why to map' were clarified, decisions were made about what was important to map and how it could be done.

Pilot transects were traced to collect the required information. The fieldwork tested various crowd sourcing applications using mobile phones to collect data. Moreover, the pilot walks served to reflect upon and refine the mapping focus, the selected variables and methods for further mapping.

(Courtesy of Development Planning Unit, UCL)

Making

How did the use of the drone shape the framing and unfolding of the project?

Rita Lambert: The use of drone enabled an up-to-date image of what was there. This in itself is a great resource for that context. In the periphery, the informal urbanisation occurring at a fast pace is a result of the lack of housing policies and affordable land for the urban poor in Lima.

(Courtesy of Development Planning Unit, UCL)

These settlements which tend to occupy steep slopes and therefore high-risk areas, are not recognized by the state and do not therefore make it onto any of the official maps.

Moreover, we could not rely on satellite images because these were outdated and did not give us the level of detail we needed to examine the territory. Here, the high quality drone images were able to show the practices of land traffickers, the opening up of new roads, as well as the chalk lines used for staking out the areas further upslope.

In the historic centre, on the other hand, there was a different problem which the drones solved. Despite being declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1991, this area is undergoing hidden changes which can go unnoticed from the street. The facades are retained while the interiors are gutter out in order to make way for the storage of containers with merchandise originating mainly from China. This illegal change of use is occurring at a fast pace and has seen the eviction of many vulnerable inhabitants. The drone images enabled one to see what was happening in the interior and how much was being destroyed. Moreover, beyond the 2D output from the drones, the 3D outputs were very revealing.

In the historic centre, where there are height restrictions, it allowed one to see the violations that occurred behind the facades. In the periphery, the 3D enabled a better understanding the whole ravine, making evident the disjunctures between the various settlements which have been planned with a singular and uncoordinated logic. This view raised consciousness of the ravine as a system of interconnected settlements which needed planning at that scale. Moreover, a detailed understanding could be attained of the difficult terrain which is negotiated by the inhabitants, the increased risk and the actual experience of dwelling the ravine. The 3D also captured the shifting borders and the threatened ecological infrastructure.

After having captured the 3D drone model, the idea was to print it using a Makerbot 2 Replicator.

(Centre for Advance Spatial Analysis)

This was indeed challenging because the drone model had to be converted into a seamless mesh. This was possible for JCM but for the historic centre, due to the shadows cast by some of the buildings, the 3D was full of holes and the volumes could not be completed. It was therefore not possible to take it to the same level of completion as the other site.

The Visual

What do conventional maps make visible and invisible and what impact did the visual outputs, the 3D map make?

Rita Lambert: All the outputs, the 2D and 3D drone images as well as the physical models and the mapping from the ground by community mappers, not only raised awareness of the inhabitants and enabled a better understanding of their territory, but it also attracted the attention of local and national authorities. The mapping is a means to open up dialogue between the inhabitants and the institutions which have various uncoordinated programs and projects in this area. It enables the integrated planning of such area and also supports the preservation and management. The project has also opened up avenues for collaboration with various public institutions in Lima where the upscaling of the methodology is sought.

Futures

Do you think emergent new mapping technologies will change the politics of spaces? Can it change how we experience of what it is to be ‘social’?

Rita Lambert: When citizens are given the possibility of producing the information they understand to be important and useful to them, and this is legitimised, it can change the politics of space. When places are defined from the outside, they also open up avenues for changes not necessarily shared by the inhabitants. When dealing with areas which are unmapped such as some of the marginalised neighbourhoods which we have been working in, making it onto the map is the first step to being recognized and to claim the right to basic services and the right to participate in decision making about the future of their area.

Click here for more info on the Remap Lima project