Part two of two articles by Katie Lloyd Thomas that explore the involvement of women in the building products industries and the architectural profession in the inter-war period. This is an abridged excerpt from the book Suffragette City: Women, Politics and the Built Environment edited by Elizabeth Darling and Nathan Robert Walker, published by Routledge in 2019.

The more observant reader might already have noticed from article part one that to the side of the photo of the ‘aristocratic lady’ in her fur coat who is about to enter the Building Centre, there is another woman. Standing up a ladder, putting the finishing touches to ‘the cartoons of building activities’ and wearing a work coat and skirt and some sparkly earrings, is the painter Marjorie Morrison. She had been the slide librarian at the AA since 1935 and worked at the Building Centre when the AA decanted to the London suburbs during the Second World War, when this photograph might have been taken. Morrison was not the only woman to be employed at the Centre.

AA graduates Mary Crowley (later Medd), Justin Blanco White and Rose Gascogine were also appointed as research assistants for Housing: A European Survey, published by the Building Centre Committee in 1936. Alma Dicker, another AA-trained architect, worked at the Centre from its inception, at first just managing one floor of the building. She also took part in organising the temporary exhibitions held at the Centre, in which capacity she oversaw the Work of Women Architects exhibition in 1936, and, as the Morning Post reported, was also responsible for the Centre’s extension in the same year:

Mr Yerbury and Miss Alma Dicker are responsible for the redecoration of the roofs and walls and this has been effected in delightful fashion wholly by means of colour values of artistic nuances. The blackening of the dome of the octagon room was a daring idea, justified by the forceful concentration of the lift from the glazed panels.

Dicker’s architectural training led her into the almost entirely male sphere of the building industry in the 1930s. Edward Bottoms, archivist at the AA, notes that she was later involved in designing stands for the Daily Mail Ideal Home Exhibition of 1939, before becoming general manager at the Centre and then emigrating to Australia in 1949 to work with the Melbourne Building Research Liaison. While journalists might have assumed the women they saw at the Centre were ‘outsiders,’ visiting only as clients, it appears that in fact a number of women worked there and must have visited in their own right as architects.

That women’s presence at the Building Centre owed not a little to director Frank Yerbury is suggested by the fact that already in the early 1920s he had made ‘Women in the Profession’ the subject of the second chapter in his Architectural Students’ Handbook. In this he argued against the received wisdom that ‘the woman student taking up architecture is necessarily bound to make a greater success of domestic work than a man’ since students of neither sex will have had any experience of household tasks before prior to their studies! In spite of some sexist assumptions typical of the period, he ended with the rousing claim that ‘the whole field of architecture is open to her … as for men.’ But women’s involvement at the Centre needs to be considered beyond its enlightened director. First, as has been well documented by historians such as Penny Sparke, Jill Seddon and Suzette Worden, the design professions as a whole were increasingly open to women in the inter-war period and quite conducive to their participation. Jill Seddon suggests that freelance design work offered women employment they could pursue even after marriage. Elizabeth Darling argues that the formalisation of architectural education and qualifications in the 1930s made the profession more accessible to women. Second, a wide range of new intermediate roles had opened up as part of the drive to stoke women’s interest in consumption. Who better to recruit women as the domestic market for the household goods being produced by the ‘new’ industries than other women who understood their needs and aspirations?

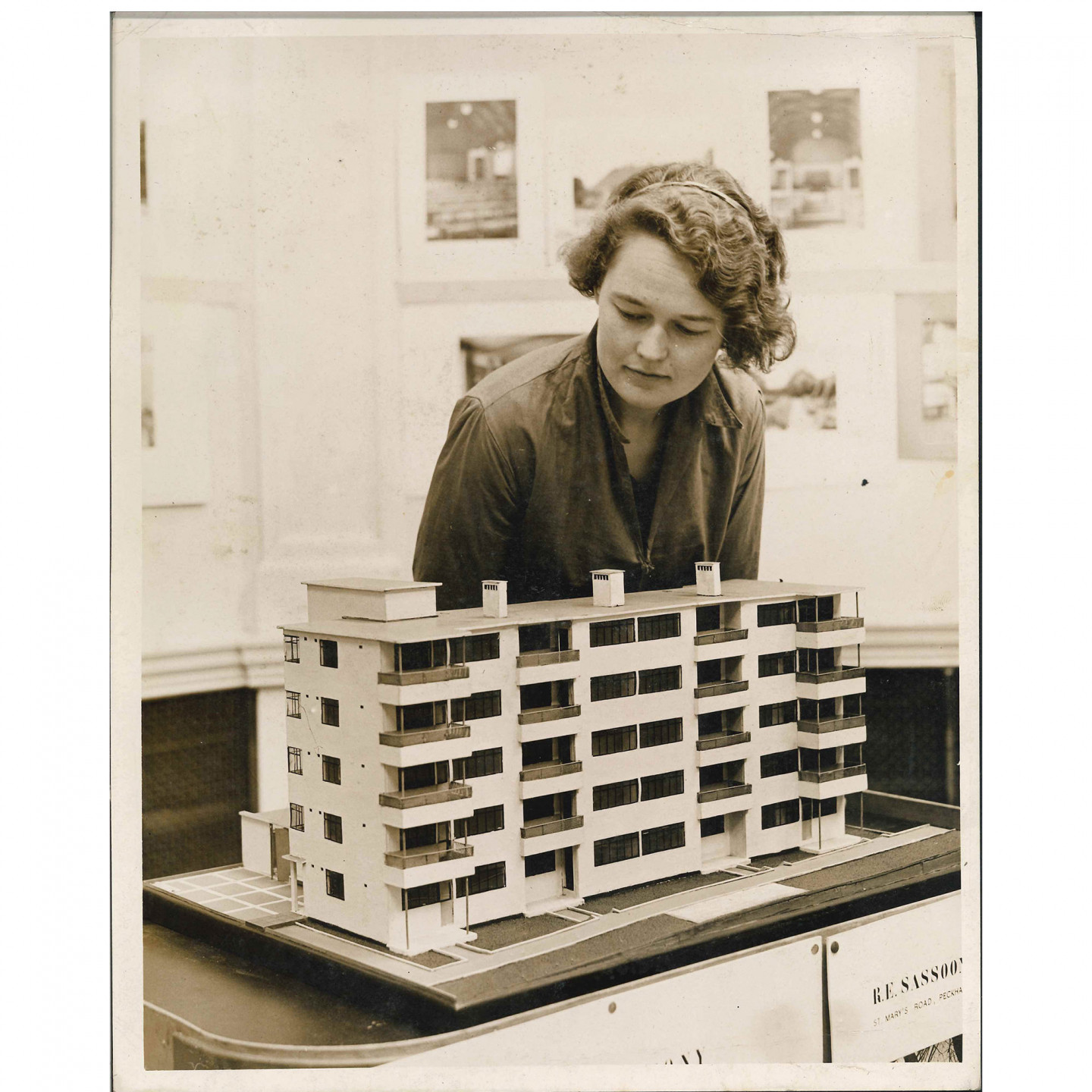

Given this, the Building Centre appears as a more natural site for an exhibition of the Work of Women Architects than it might at first have seemed. No exhibition catalogue has yet been found, and only two original photographs remain to give us any sense of what the exhibition was like. In each image we see the face of a woman peering at a model. She is not a visitor or an ‘outsider,’ but one of the exhibitors, the architect and sometime employee of the Centre, Mary Crowley (1907–2005). From the extensive press coverage of the exhibition, we can piece together a list of most of the thirty or so exhibitors, who had been selected from a call for contributions set up by Dicker.

Although many of the projects on display were houses, other non-domestic schemes ranged from Elisabeth Scott’s design for a Coffee Stall on Hampstead Green, described by one reviewer as ‘surely one of the purely most masculine buildings it is possible to imagine,’ to a private zoo and a printing works by Aiton & Scott, Hilda Mason’s design for a combined church and mission hall using reinforced concrete, in Felixstowe, a roof garden and nursery on top of a block of flats by Janet Pott and Alison Shepherd, as well as a number of projects by Jane Drew. Larger schemes on display included Elizabeth Denby’s design with Maxwell Fry for modernist flats in Peckham, a group of almshouses by J.E. Townsend and Swarland, an austere resettlement village of seventy-seven houses, store, wood workshop and village hall built in Northumberland for the Fountains Abbey Settlers Trust and designed by Molly Procter-Reavall to house unemployed workers from Newcastle upon Tyne. As well as Mosely’s Electrical Housecraft kitchen, the exhibition featured an all-electric house designed by Claire Nauheim. One journalist mentioned Dicker’s setting out of ‘the building materials and fittings displayed,’ as a ‘novel type of work’ alongside the more conventional forms of architectural work exhibited.

Once again the national press, trade journals such as The Builder and women’s magazines gave the exhibition much enthusiastic coverage. Reporting in the architectural press was, however, scant and limited to tiny paragraphs in the journals’ news and events sections, in which comments were often disparaging. The only comment recorded from inside the profession – a professor at a leading school of architecture – claimed that women were not likely to be as first rate or as creative as men. The impression is that this celebration of women’s new entry and contribution to the profession was little supported by most architectural educators and practitioners. Instead, in creating a space in which women were welcomed as consumers of building products and of electrical appliances, it was the Building Centre that established conditions that supported their work in the building and design industries.