Flooding is an increasing challenge to many towns and cities but the resources required to fix the problems need better thinking and solutions. Recent events provoked a fresh wave of proposals involving architecture, engineering and policy ideas. Our editors have sifted the contenders and below is a briefing on the more compelling ideas championed by experts in the field.

1. Move Flood Defences

By the time the rainwater has flowed down from the uplands to the valleys and rivers it is already too late, argues Alex Stephenson, who aside from being the Market Development Director at Hydro International who provide an upland system, has also been Chair of the British Water Sustainable Water Management (SuWM) Focus Group for over 10 years. Stephenson told WaterBriefing that, “Proven vortex technology such as that used in the White Cart Water flood alleviation scheme in Glasgow is already helping to protect vulnerable communities, by using an upstream solution that uses no power, requires minimal maintenance and creates wetland biodiversity.” While Stephenson isn’t a disinterested party, after the project became fully operational the White Cart Water project won the Environmental Award in the British Construction Industry Awards in 2012.

2. Trees and Green Roofs

It may be an incredibly old technology, but everyone from environmentalists to governments and urban planners are agreed that trees are part of the solution to flooding. The Woodland Trust commissioned a case study of Pontbren farmers in Wales who, by planting trees over the last 15 years, have not only improved soil by preventing the runoff washing away vital nutrients but also increased infiltration of water into the soil by a factor of 60 compared to nearby tree-free sheep-grazing pasture. Modelled across the entire area of study, the impact of trees was shown to potentially reduce peak stream flows by up to 40%. With more evidence supporting the value of trees, the European Environment Agency 2015 report Water-retention of Europe’s forests shows that water retention increases in relation to the density of a forest. “Compared to basins with a forest cover of 10%, total water retention is 25% and 50% higher in water basins where the forest cover is more than 30% and 70%, respectively.” GreenBlue Infrastructure are just one consultancy providing a range of useful documentation around the uses for urban tree planting in projects and case studies from Blackheath and Bradford in the UK to Chicago, Copenhagen and Toronto. Additionally, a report from the Forestry Commission highlights US data showing that even the humble yard tree “can intercept 760 gallons (3455 litres) of rainfall in its crown, thereby reducing polluted stormwater runoff and flooding.” In order to make the most of trees, to help policymakers and citizens understand the exciting changes trees can make to the environment is to start seeing them not as ‘nature’ but seeing them as an exciting technology capable of extraordinary uses.

3. Sustainable Drainage

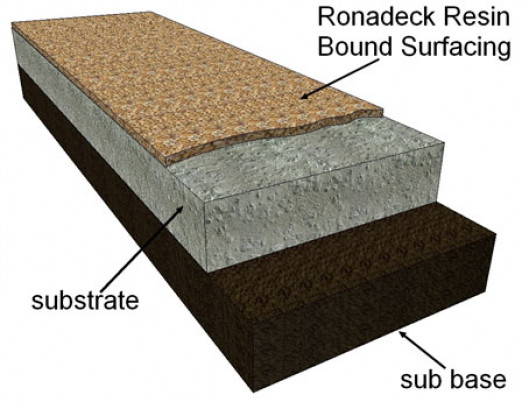

Trees may be part of any Sustainable Drainage System (SuDS), and sustainable drainage has been on the agenda. The UK Water Partnership’ 2015 document Future Visions for Water and Cities estimates the value of UK water infrastructure to be £400 billion, while the OECD believes that the biggest share of infrastructure investment will soon be water-related. Emphasizing just how important water security has become, the report says, “For just OECD countries and Russia, China, India and Brazil, water spending in 2025 will top $1 trillion - nearly triple the amounts needed for investments in electricity or transport (World Bank 2012).” The report is a useful compendium of ideas that have been floating round or put into practice, such as buildings with stilts that allow the bottom floor to be flooded, mega storm tunnels such as the Thames Tideway Tunnel (see the DEFRA report), and of course SuDS. “Requirements include: creation, preservation and restoration of ponds, woodlands and wetlands; green roofs; sustainable drainage systems (SuDS); and permeable surfaces for domestic gardens, both in urban centres and in upstream catchments.” The Landscape Institute have been champions of the SuDS approach and their December 2014 briefing took the Coalition government to task for reducing the requirements on homebuilders to provide “wetlands, reed beds, drainage channels and porous driveways” which are all highly effective tools to prevent run-off flooding.

The report cites SuDS hero cities such as Philadelphia, which has been using a SuDS strategy both for practical and financial reasons – and shows how retro-fitting is a cost-effective strategy for a major city. The 25-year Green City, Clear Water project is enabling them to avoid the $8-9 billion cost of a sewage treatment plant that would, “otherwise be required to deal with their problems of flooding and illegal discharge of sewage into the river system.” The city’s Philly Watersheds website is both a great resource and an effective campaigning resource for citizens. The Susdrain website is a useful UK resource.

4. Waterborne Architecture

The Boston Redevelopment Authority recently held a $20,000 competition called Boston Living With Water, attracting proposals from designers and architects around the world to help rethink a city which, like many others, faces the prospect of flooding as a consequence of climate change.

(From the Boston Living With Water competition)

The submissions highlight a trend towards adaptation, where buildings have higher…., where bridges become a central feature of life – walkways and transport systems – and canals and boats are developed as new infrastructure, alongside floating and amphibian buildings.

(From the Boston Living With Water competition)

Though visionary, these are longer term development projects and also highlight a subtle shift from mitigation to adaptation. Dutch firm Waterstudio around for their innovative waterborne architecture worked with UNESCO and a local non-profit organization to develop what are called City Apps – floating shipping containers designed to float alongside ‘Wet Slums’, the shanty towns that float on water. The City Apps are designed to provide services such as food, sanitation, shelter and energy, and classrooms for education. The work that Waterstudio do is an indicator of the leading edge of addressing the challenge of floods – it’s about an evolutionary adaptation of living. Ken Althuis of Waterstudio calls what they do Aquatecture.

There has been a strategic shift from prevention to mitigation to adaptation. Carl Turner, who worked with The Building Centre and Arup on the shipping container project for A House for London, developed a floating house last year.

Even for the most optimistic estimates of climate change, many cities will need to rethink and reframe inherited relationships with land and water.

5. Information, Communication and Engagement

Many of the ideas and innovations suggested have been thought through and developed by experts and policy-makers, and can make a difference. However, the political momentum required for decision-making on the scale required remains absent; citizens aren’t engaged enough. However, prototype technologies such as the Local Environmental Virtual Observatory Flooding Tool, which proposed using cloud technology using live data, modelling and webcams, give local ‘stakeholders’ such as farmers and residents up-to-date information on land management and land usage, with the tech and data that enables them to develop scenarios. It’s partly about better prediction, but the real value lies in citizen engagement.

6. Domestic change

At the domestic level, governments and architects have been advising citizens on small changes households might make. Six Steps to Property Level Protection, produced by The University of Manchester and The Building Research Establishment, advises householders to prevent backflow through toilets and plugholes via non-return valves, or installing flood doors and sump and pump systems to take the water away. A study in Germany by the European Commission’s Science for Environment Policy revealed that “homeowners who had suffered from financial or health damage in the past from flooding were 21% more likely to implement their own flood mitigation measures…Homeowners were up to 12% more likely to implement flood mitigation measures if they expected climate change to increase flood risk over the coming decades.” Underlying these figures which suggest that past experience simply isn’t delivering change, is a belief by 30% of people that the government provides funds for flood damage – though there is no official regulation.

Architects are looking to make similar micro-level changes in their structures. In the US, after Hurricane Sandy in 2012, FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency) raised the previous flood level plain (which had existed for 100) years by a foot, reported Metropolis magazine on a new 11 story luxury development in Manhattan designed by Steven Harris Architects. They extended the foundation walls by 12 feet above ground level, installed a waterproofed vault containing the electrical systemand mechanical equipment whose entry is through submarine-like bulkhead doors, and stackable aluminium “fast logs” barriers sealed with high-density, closed cell neoprene sponge. In Imagining the Future City: London 2062, a book emerging from UCL’s Grand Challenge of Sustainable Cities project, environmental architect Sofie Pelsmakers outlines four typologies of buildings suited to landscapes where water is a more common feature; the sacrificial basement; building on stilts; floating buildings, and wet-proofed buildings.

All of the briefings, reports, books we looked at believed the increased regularity of floods and the likelihood of sea-level rises impacting coastal towns and cities, means we will need both short term and long-term solutions: defences and deployments of technology that will mitigate damage now; and solutions which offer a different vision for our towns and cities, different kinds of housing, transport and economy that for many area will increasingly be organised around living with water.

_(8).jpg)