Dense + Green is a major overview celebrating innovative architecture, skyscrapers and ecology. It tracks the new thinking around urbanism, materials and ideas of nature.

The size and weight of this book, the scale of the high rises, the way in which the name of the book appears in huge white-on-black type on the second opening (Dense + Green) gives the ‘green’, ecological theme an unusually monumental feel. When deep down, ecology still resonates culturally with notions of the ‘pastoral’, with ‘landscapes’ with quasi-spiritual notions of nature, the slab-like design of Dense + Green: Innovative Building Types for Sustainable Urban Architecture is a refreshing provocation to rethink ecology.

(Mountain Dwellings, Big/JDS Architects, 2008)

The book wraps text in rich array of supporting visual evidence, and amongst others includes chapters by: Thomas Schroepfer, (Professor and Associate Head of Pillar of Architecture and Sustainable Design at Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD), founded in collaboration with MIT) on the ‘The Dense and Green Paradigm’ and ‘Dense and Green Building Typologies’; Kees Christiansee (Professor of Architecture and Urban Design at ETH Zurich and Programme Leader of ETH’s Future Cities Laboratory in Singapore) on ‘Green Urbanism’; and Practice Reports by the likes of Foster + Partners on ‘Environmental Performance Optimization on the Urban and Building Scale’ and MVRDV on ‘New Nature’.

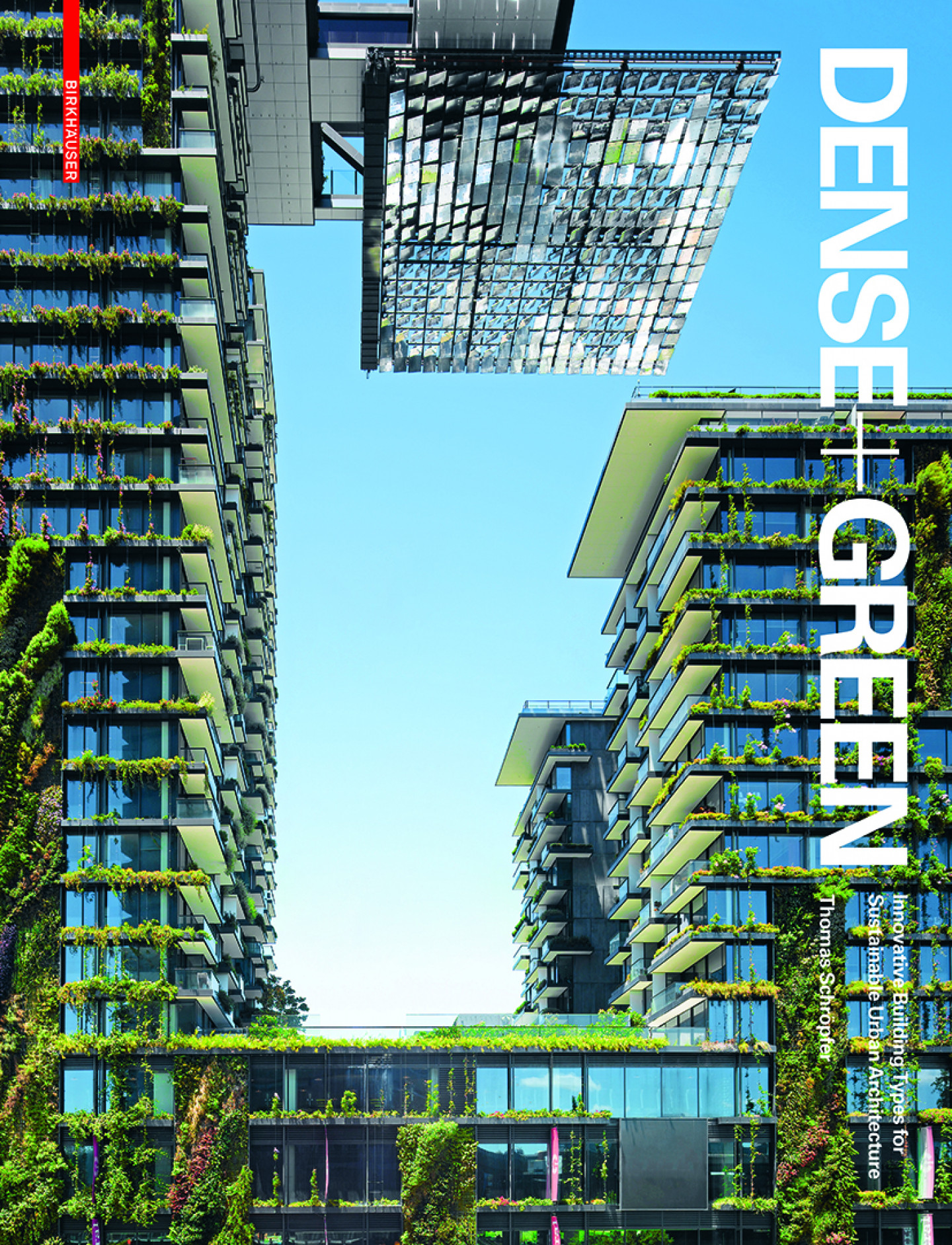

(One Central Park, Ateliers Jean Nouvel/PTW Architects, 2014)

Schroepfer stakes out his hypothesis in the opening chapter in a historical survey of urban architecture’s expression of and negotiation with ideas of nature – from the mid-town modernism of Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo’s Ford Foundation Building (1968), to Kisho Kurokawa’s Metabolist Nakagin Capsule Tower (1972), to Archigrams’ Sponge City project (1974).

(Left to Right: Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo’s Ford Foundation Building 1968; Kisho Kurokawa’s Nakagin Capsule Tower, 1972; Arata Isozaki, Clusters in the Air, 1962)

Schroepfer's talent for picking out the evolving architectural philosophies alongside the rich visuals makes for engaging storytelling. He highlights the revisionism of Rem Koolhaas’ OMA, in recent work such as the CCTV project in Beijing, or the Togok (XL) Towers project in Seoul – “Rather than articulating density through the traditional heroics of the skyscraper, there is an essential, almost ironic dismantling of the skyscraper typology.” He sees this rearrangement of mass in buildings such as OMA Buro Ole Scheeren’s Interlace Singapore project (a 1,000-unit residential building), whose daring restacking of the skyscraper facilitates its green features.

(The Interlace, OMA Buro Ole Scheeren, Singapore, 2015)

Indeed, by the end of the book, in a chapter on ‘Future Trajectories’, Schroepfer notes how we also need to be attentive to the discourses around how dense and green building need to be addressed – the concepts of ‘skyscraper’ and the ‘high-rise’ may reflect zoning requirements, but they also connote commercial and corporate power, and the cultural status of the architect. And yet the towering experiments of practices such as MVRDV show how architectural form can challenge and provoke the public imagination around how we can live.

(Left: Folie Richter, MVRDV, Montpellier, rendering, 2014.Perruri 88, MVRDV, Jakarta, rendering, 2012)

Indeed, as MVRDV argue in their ‘New Nature’ chapter, “The wider public should become aware that sustainability is enjoyable and not a sacrifice, that it is possible to combine lower resource consumption with more ambition, more comfort, higher density and higher quality of life…This relatively new pattern of artificialised nature or naturalised urbanity offers new fields of experimentation.”

Indeed, like “High-Rise” with its corporate associations, we may need to invent a different word or idea for “sustainability” – not a word that spells ambition or higher quality of life.

(Vertical Garden House, Office of Ryue Nishizawa, 2011)

Dense + Green is a carefully argued book that brings the reader up to date on the thinking, practices and concerns around ecology and architecture. It is a reminder that these are shifting debates with a vocabulary (architectural and political) that is up for debate. The book still has one foot in the camp of the heroic architect – far removed from the work of Assemble or the urban engagement of Ezio Manzini and Muki Haklay. But it is a reminder that socially ambitious architects and clients can make spaces and material ideas for citizens to be inspired and provoked. Additionally, it is not just citizens, but organisations with wealth and power who need to be reminded in their workspaces of the social world in which they exist, and bold architecture does this far more effectively than any corporate branding or internal emails about corporate social responsibility. As Ada Louise Huxtable remarked of the Ford Foundation building, it was “a horticultural spectacular and probably one of the most romantic environments ever devised by corporate man," a building that was "aware of its world."

Dense + Green: Innovative Building Types for Sustainable Urban Architecture is published by Birkhäuser