In this interview with a first class Renewable Energy Graduate from the University of Exeter, Dr Matthew Trewhella, Managing Director at Kensa Contracting, shares his thoughts on the future of the gas network and explores means to decarbonise the national grid in future heat frameworks, including the role of hybrid heat pumps (a gas boiler coupled with an air source heat pump) compared to ambient shared ground loop arrays and ground source heat pumps.

On the future of the gas network and the National Grid

What do you think the future for the gas network will be in the UK, in terms of renewable gas content and future gas prices?

It seems likely by 2035 there will be significantly less gas supplied into the grid – most estimates I see suggest around 50%. It is also likely that this lower level will be made up of at least some biogas. The last report I saw was suggesting around 90% – that means natural gas would be at 5% of its current levels.

What impact will the uptake of heat pumps have on the National Grid?

Overall, adding more heat pumps to the grid will increase electrical demand and overall generating capacity could be a limiting factor on how quickly heat pumps could be deployed.

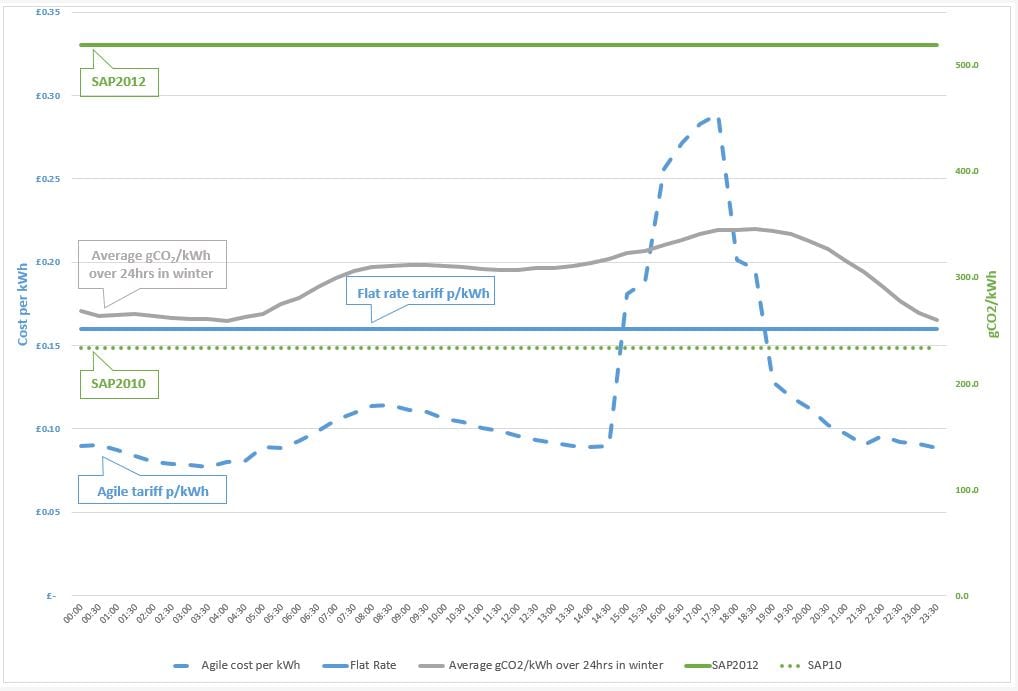

However, when you combine heat pumps with smart controls, remote grid balancing and time of use tariffs, heat pumps can have a positive effect on the grid by turning on when there is overgeneration (instead of turning wind turbines off like we do now) and by turning the heat pumps off when the grid is under strain. This is particularly true for ground source – because the source temperature is more stable, they can be run overnight without loss of efficiency. Our grid generally has most excess capacity overnight – some of the variable tariffs actually go negative on some nights so people can get paid for running the heating. It turns out this is cheaper than paying people to turn wind turbines (and other generators) off.

There will undoubtedly be some upgrades needed – particularly where the existing wiring wouldn’t meet current standards. In particular where there are “looped” supplies which are basically multiple properties fed from the same wire. These looped supplies only really work for gas heated properties with low electrical loads – you couldn’t run an electric shower for instance.

The National Grid have stated they are ready for the uptake in heat pumps and have included hybrids in their Future Energy Scenarios report; what are your thoughts on this?

I think that the National Grid and the distribution networks are well prepared – at least for the 2.5 million expected heat pumps by 2030. After that, we’ll see.

It is sensible for them to include hybrid heat pumps as there has been a lot of talk in Whitehall about hybrids. Even though I am not a fan of the hybrid idea, I am not too put off by National Grid preparing for them. The same preparations would also make the grid ready for ground source which I think is the better solution.

What are your predictions or recommendations for the future energy policy for heat pumps and decarbonising the heating network in general?

The rapid recent decarbonisation of the electricity grid now means that electrification of heating shows significantly more promise than decarbonisation of the gas grid. Ground source heat pumps give the lowest running costs (because of highest efficiencies) and the lowest grid impact (because they can be run flexibly at any time of day or night without loss of efficiency).

Daily Average Cost & Carbon Of Electricity*

A pure ground source heat pump conversion from mains gas is currently much more expensive initially than an air source heat pump/gas hybrid. However, once you model the costs over a period in excess of 12 years (i.e. you encompass the replacement costs of the gas boiler and ASHP) then GSHPs become the lowest cost option.

What role do you think hybrids will play in the decarbonisation of the UK’s heating network?

I would like to see efforts and particularly Government funding and initiatives concentrated elsewhere on a more long term solution. The idea of hybrids is gaining traction at high levels and there may well be significant deployment initially until better alternatives start to overtake them.

On the FREEDOM Project

The FREEDOM Project was a 27 month research programme to investigate the capability, affordability, and attractiveness of gas hybrid heat pump systems in domestic properties.

The companies that carried out the FREEDOM project strongly believe that hybrids are the future of decarbonising the UK’s heating network, what is your opinion on this statement and the FREEDOM project itself?

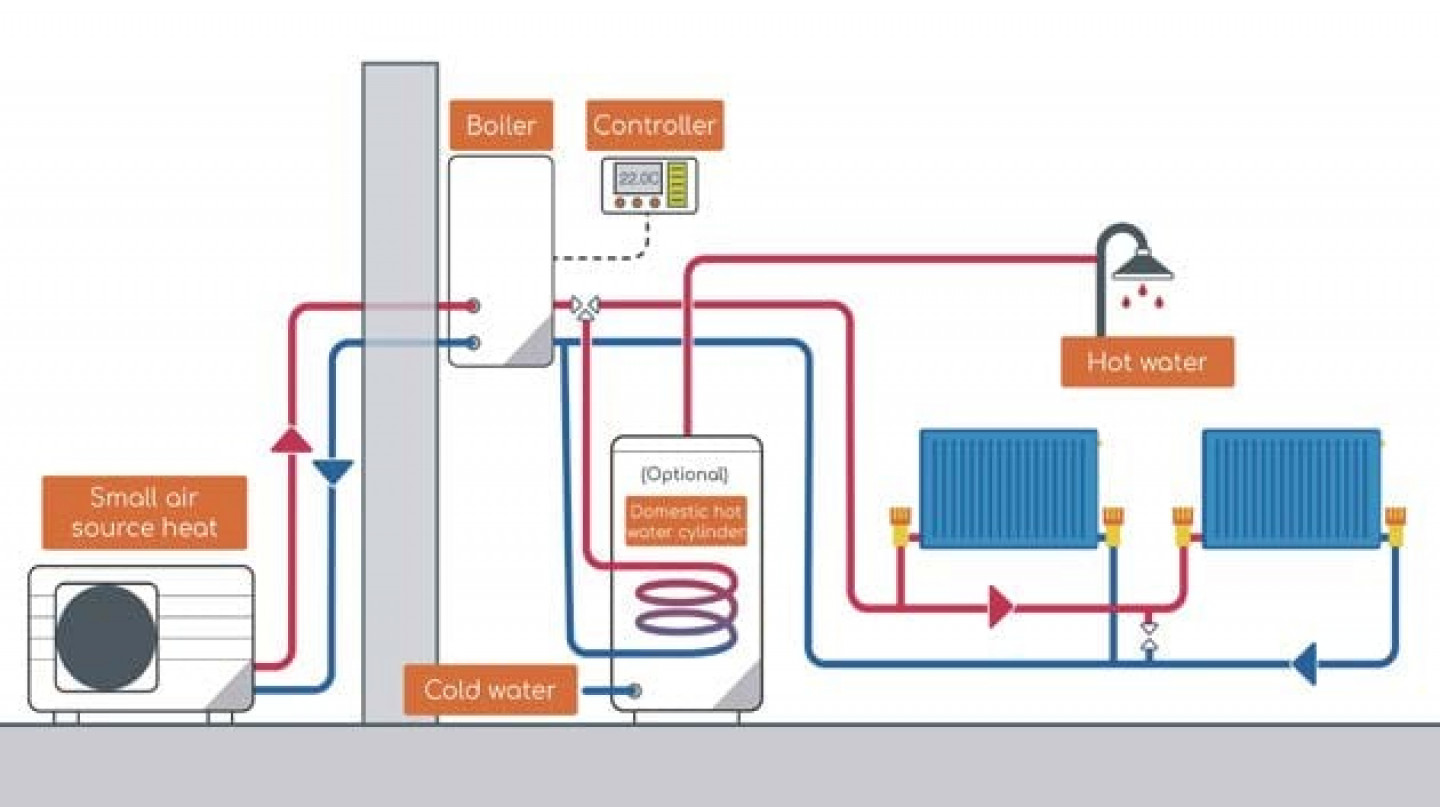

Given that the gas grid is likely to supply only 50% of the energy it currently does by 2035, then it might initially seem logical to assume that the best way to handle this would be to fit every property with an air source heat pump (ASHP) as a hybrid system with 50% of the heating and hot water load handled by each appliance.

However, this commits every property to live with 2x service and maintenance regimes every year, 2x replacement costs of relatively short lived appliances typically every 10 years, and 2x grid connection standing charges.

So while it would achieve some rapid decarbonisation it would be a short-term approach with very little legacy created by the capital expenditure.

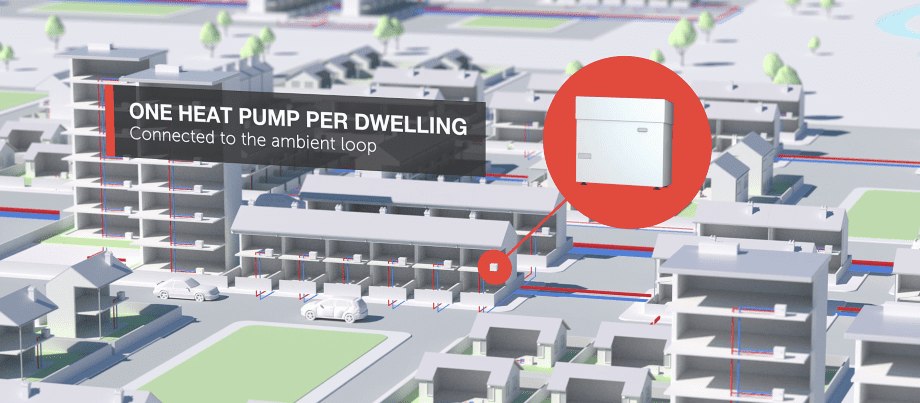

I suggest a more sensible approach would be to invest the same capital amount of removing 50% of the properties from the gas grid entirely. You would achieve higher carbon savings, lower running costs and then be left with a single, low maintenance, long life appliance and the ground array infrastructure would be in place for a century or more leaving a highly beneficial long-term legacy.

With careful planning and zoning, this “managed retreat” approach from the gas grid would involve disconnecting in areas – either those with the highest air quality problems or the best geological conditions.

On energy storage and smart controls

A key advantage of hybrids is their flexible heating modes (parallel, switch, continuous, twice a day); for example, they can be run continuously whilst allowing for twice a day heating. How effective do you think these will be in terms of homeowner acceptance, understanding and their impact on the National Grid?

Hybrids are flexible and that is their main benefit. However, it is possible to obtain just as much flexibility using ground source heat pumps and thermal storage and this would result in significantly lower overall carbon emissions, bill savings and maintenance costs.

In terms of homeowner acceptance, they mostly just want their property to be warm when they want it and for the heating to cost as little as necessary (i.e. no waste). If the controls achieved this and allowed the householders to make changes when their lifestyle or schedule changed then acceptance levels will be generally high. In the hybrid case, it would be important to give detailed billing information breakdown – i.e. showing what percentage of the heat was delivered by ASHP/gas and how much has been saved – ideally by carbon and running costs.

Grid impacts are where hybrids potentially score highest, however as with running costs and carbon savings, the same or better grid balancing effects can be achieved using ground source heat pumps and local storage.

Hybrid smart controls allow demand side response and interventions such as demand constraints, what are your thoughts on these? Will the National Grid require this ability in the future?

The controls are great and I am grateful that they exist because it is exactly the same hardware (although with different programming/machine learning) that is required to carry out demand side response and grid balancing with ground source heat pumps.

Hybrids have the potential to reduce energy bills for homeowners, could this steer uptake towards hybrids?

At the moment, air source heat pumps are more expensive to run than gas boilers so I am not sure I share their potential to reduce bills. Despite the urgent nature of the need to tackle climate change, bill reduction will remain the most significant driver for homeowners. Hybrids will have to be very clear about the objectives of the control systems – if they are optimised to deliver the largest carbon savings then the gas boilers will run infrequently – perhaps 10-20% of the time. If they are optimised to deliver the lowest running costs then the air source heat pump will run infrequently (potentially only at night which is when they are least efficient).

Compare this to ground source heat pumps with smart meters and time of use tariffs which would give bill savings of 25% and carbon savings of 70% compared to mains gas.

On public perception

The FREEDOM project concludes that hybrids are ready for immediate deployment to act as a flexible transition technology whilst the National Grid undergoes changes; what are your thoughts on the feasibility of immediate widespread deployment of hybrids in terms of public awareness of the technology, willingness to co-operate, ease of installation, understanding of smart meters and a potential rate of deployment?

Currently, the heat pump industry (air source or ground source) would need to undergo a rapid expansion from 20,000 units per year to over 300,000 units per year in order to facilitate a flexible grid transition. This is going to pose a significant challenge in terms of scaling up production and up-skilling existing installation contractors. The industry is ready for this but would need to start ramping up rapidly for several years ahead of the final required deployment rates.

There will undoubtedly be resistance to air source heat pumps, because of the visual and noise impacts. Generally speaking air source heat pumps are more expensive to run than gas boilers at current prices and this will be another source of resistance.

The smart meters themselves should generally be accepted provided they were reliable (which has been an issue with the first generation) and regular reports were generated showing people how much they had saved.

Smart controls are relatively new for homeowners; how will homeowners react to them in terms of changing their energy use patterns to work around the National Grid and understanding how they work?

Making smart controls easy to understand and use will be absolutely key to wider deployment.

From what I have heard, this part of the FREEDOM project did cause some issues with end users.

Kensa are just about to start on our own smart control field trial and I am putting a lot of upfront time in to evaluating the different smart controls to make sure that we install controls that are designed around the user rather than an engineer. Our front runner right now is https://www.switchee.co/

On future innovations and markets

Future innovations such as new refrigerants could improve the performance of heat pumps, which future innovations (if any) do you think will be emerging in the future?

Generally the challenge within the heat pump industry is to maintain heat pump efficiency while moving to lower GWP (Global Warming Potential) refrigerants rather than to improve efficiency.

The largest impact potential innovation is likely to come from overall system design rather than heat pumps themselves. The most promising is combining a GSHP with phase change thermal storage, smart controls and time of use tariffs. These have the capability of providing running costs savings of 25-35% and carbon savings of 65-80% compared to mains gas.

What do you think will happen to the price of heat pumps in the future, including smaller heat pumps (under 5kw)?

The price will undoubtedly come down. This will partly be because of volume discounts and refinement of manufacturing processes. It will also be partly due to the sales process being simplified as the knowledge increases and the products become more mainstream and understood. In the case of ground source, drilling companies currently operate nationally and have to switch between many diverse roles – they could be carrying out site investigation one day and ground source boreholes the next – and this carries inefficiencies. Once the market is large enough, there will be specialised ground source drilling rigs that only cover small areas and we expect this will reduce the cost.

*Daily average cost and carbon graph: Base electricity charges based on Sheffield averaged on the Big Six once a month – average electricity cost per kWh (www.ukpower.co.uk/home-energy/tariffs-per-unit-kwh, www.nottenergy.com/energy_cost_comparison). Octopus Agile Tariff (average over 24hrs). Average CO2/kWh over 24hrs in winter (www.carbonintensity.org.uk)

Credit: Questions complied by Olivia Stokes, third year Renewable Energy student at Exeter University (2019).